Introduction to Pointillism

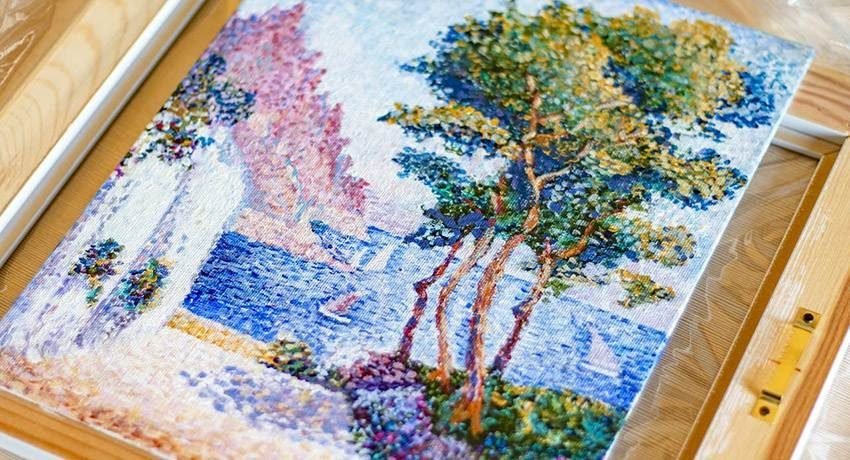

Pointillism is a distinctive and revolutionary painting technique that emerged in the late 19th century as an offshoot of the Impressionist movement. It involves the application of small, distinct dots or dabs of pure color to a canvas in patterns to form an image. Unlike traditional painting methods that involve mixing pigments on a palette, Pointillism relies on the viewer’s eye and mind to blend the color spots into a fuller range of tones and hues. This method, developed primarily by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, is rooted in scientific theories of color and optics and represents a significant evolution in modern art. Pointillism exemplifies a fusion of artistic creativity and scientific precision, offering a unique way of interpreting light, color, and form.

Historical Context and Origins

The origins of Pointillism can be traced back to the late 1880s in France, a period characterized by intense experimentation in art. It was a time when the limitations of traditional Impressionism began to be challenged. Impressionist artists sought to capture fleeting moments and effects of light through loose brushwork and vibrant color palettes. However, Georges Seurat, a French Post-Impressionist painter, believed that Impressionism lacked the structure and rigor needed to create a lasting visual impact. Influenced by scientific studies of color and perception, Seurat developed a more methodical and precise approach to painting, which he called “Divisionism.” The term “Pointillism” was initially coined by critics in a somewhat derogatory tone, but it has since been embraced as a defining term for this innovative technique.

Scientific Foundations

Pointillism is deeply rooted in scientific research, particularly the color theories developed by Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood, and Charles Blanc. Chevreul’s “law of simultaneous contrast” posited that the perception of a color is affected by the adjacent colors. Rood, an American physicist, emphasized the optical mixing of colors, where closely placed small dots of different hues blend in the viewer’s eye, producing a luminous effect. These theories had a profound influence on Seurat and other Pointillists. Rather than physically mixing paints, Pointillist artists placed complementary colors side by side in tiny dots or strokes. When viewed from a distance, the human eye blends these discrete points of color, resulting in a shimmering, dynamic visual experience. This method not only enhanced luminosity but also brought a new level of precision and intentionality to color application in art.

Technique and Execution

The execution of Pointillism requires meticulous attention to detail, patience, and a deep understanding of color theory. Artists using this technique apply tiny, precise dots or dabs of paint to the canvas using small brushes, often with a consistent shape and size. The goal is not to create texture through brushstrokes but to build an image through the strategic placement of color. The choice of colors is critical; artists often use complementary and contrasting colors to create a vibrant effect. For instance, to depict a shadowed area, a Pointillist might place cool blue dots near warm orange ones, allowing the eye to interpret depth and shading through optical mixing. The success of a Pointillist work depends on the viewing distance; up close, the image appears as a field of colorful dots, but from afar, the dots blend to reveal a cohesive image. This technique demands careful planning and a mathematical sense of composition, as the placement of each dot contributes to the overall harmony of the piece.

Georges Seurat: The Pioneer

Georges Seurat is universally regarded as the father of Pointillism. His most iconic work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), is a monumental example of Pointillism and one of the most analyzed paintings in art history. Seurat spent over two years completing this large-scale work, applying millions of tiny dots with scientific precision. The painting depicts Parisians leisurely enjoying a park by the River Seine, yet its deeper significance lies in its structure and technique. Every color in the painting was deliberately chosen based on optical theory, with Seurat striving for a harmonious balance of hue, light, and form. His disciplined approach was in stark contrast to the spontaneity of the Impressionists. Seurat’s work marked the beginning of Neo-Impressionism, a movement that sought to impose order and clarity on the fleeting impressions of modern life.

Paul Signac and the Expansion of Pointillism

Paul Signac, another key figure in the development of Pointillism, was a close associate of Seurat and an ardent supporter of Neo-Impressionist principles. After Seurat’s untimely death at the age of 31, Signac became the leading advocate of Pointillism, both through his artwork and his writings. His book, From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899), provided a theoretical framework for the movement and emphasized the importance of scientific approaches in art. Signac’s work is often more colorful and expressive than Seurat’s, reflecting his interest in the emotional power of color. His landscapes and seascapes, such as The Port of Saint-Tropez, are celebrated for their radiant color schemes and vibrant light effects. Signac adapted the Pointillist technique to his own style, using larger, more visible dots and a broader range of hues, which contributed to the evolution of the method into more expressive forms.

Other Influential Pointillist Artists

Although Seurat and Signac were the leading figures, several other artists adopted and adapted Pointillist techniques. Camille Pissarro, an established Impressionist, briefly experimented with Pointillism in the 1880s, producing works that merged his pastoral themes with the precise dot application of Neo-Impressionism. Henri-Edmond Cross was another notable practitioner whose works reflect a lighter, more decorative use of the Pointillist method. His paintings often convey a dreamlike quality, with bright, almost mosaic-like color fields. Van Gogh, though not a strict Pointillist, was influenced by the technique during his time in Paris, incorporating small, rhythmic brushstrokes in works like Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat. The cross-pollination between Pointillism and other styles helped to spread its influence across Europe and into later movements like Fauvism and Cubism.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its intellectual rigor and visual appeal, Pointillism was not universally accepted. Many critics in the late 19th century dismissed it as overly mechanical or devoid of emotional depth. The painstaking nature of the technique also made it less accessible to many artists, limiting its widespread adoption. Some felt that the focus on optical precision came at the expense of spontaneity and personal expression. Nevertheless, the scientific approach to color and the meticulous construction of images attracted artists who valued structure and innovation. Over time, the initial skepticism gave way to a broader appreciation of the method’s unique contributions to modern art.

Evolution and Variations

Pointillism evolved over time as artists modified and interpreted the technique to suit their own artistic visions. While Seurat remained rigid in his application of dots, later artists such as Signac, Cross, and Theo van Rysselberghe introduced greater fluidity and expression into the technique. Some began to use brushstrokes that resembled small tiles or mosaic patterns rather than dots. Others expanded the color palette to include more intense and non-naturalistic hues. This evolution allowed Pointillism to adapt to changing artistic currents, influencing movements such as Fauvism, which also emphasized vivid colors and formal structure. By the early 20th century, Pointillist methods had been absorbed into broader modernist experiments, paving the way for abstraction and the avant-garde.

The Role of Perception and Viewer Interaction

A defining feature of Pointillism is the active role of the viewer in completing the image. Unlike traditional painting, where the artist blends colors and defines forms directly, Pointillism relies on the viewer’s eye to mix the colors optically. This interactive quality enhances the sense of depth, movement, and vibrancy in a painting. The viewer becomes an essential participant in the creation of the visual effect, experiencing subtle changes in color and form depending on the viewing distance. This concept anticipated later developments in art, such as Op Art and interactive installations, where perception and viewer experience are central to the artwork’s impact.

Color Theory and Optical Mixing in Depth

At the heart of Pointillism lies the principle of optical mixing. Instead of physically mixing blue and yellow to produce green, for instance, a Pointillist artist places blue and yellow dots side by side. From a distance, the eye blends these colors to perceive green. This technique enhances brightness and purity, as the colors retain their individual intensity rather than becoming duller through physical mixing. Optical mixing also allows for more dynamic contrasts and vibrant surfaces. The use of complementary colors, such as red and green or blue and orange, can intensify visual effects and create a shimmering quality on the canvas. Understanding the nuances of optical mixing is essential to mastering Pointillist techniques and achieving the desired luminous effects.

Applications Beyond Painting

Although primarily associated with painting, Pointillist principles have influenced other art forms and disciplines. In graphic design and digital imaging, the use of discrete color units (pixels) to create images is conceptually similar to Pointillism. Contemporary artists and designers often reference Pointillist techniques in print media, textile design, and animation. Even in music, the term “pointillism” has been borrowed to describe compositions characterized by isolated notes and punctuated rhythms, as seen in the works of composers like Anton Webern. The universality of the Pointillist principle—constructing a whole from discrete parts—demonstrates its relevance beyond traditional fine art.

Legacy and Influence

The legacy of Pointillism is profound and far-reaching. It challenged conventional notions of painting and introduced a systematic, almost scientific approach to art-making. By integrating color theory, optical science, and precise technique, Pointillism bridged the gap between Impressionism and modernist abstraction. It influenced a range of movements, from Fauvism and Cubism to Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. Artists like Henri Matisse, Robert Delaunay, and Roy Lichtenstein drew inspiration from Pointillist methods, whether in their use of color, pattern, or compositional structure. In the digital age, the principles of Pointillism resonate in pixel-based imagery, data visualization, and algorithmic art, reaffirming the technique’s enduring relevance.

Modern and Contemporary Pointillism

Contemporary artists continue to explore and reinterpret Pointillism in novel ways. Artists such as Chuck Close used grid-based, dot-like applications in photorealistic portraiture, blending modern technology with traditional Pointillist logic. Others incorporate the technique into multimedia installations or interactive works, using digital dots, lights, and projections. The accessibility of digital tools has made Pointillist-inspired art more popular in online and commercial platforms, where resolution and pixel manipulation echo the original Pointillist concept. Meanwhile, art educators continue to teach Pointillism as an entry point into understanding color theory, composition, and the science of perception.

Conclusion

Pointillism stands as one of the most intellectually and technically demanding art techniques in history. Born out of a desire to bring order, clarity, and scientific rigor to the chaos of Impressionism, it transformed the way artists thought about color, light, and perception. Through the visionary efforts of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, Pointillism introduced a new visual language that continues to influence art and design to this day. More than just a technique of placing dots on canvas, Pointillism represents a profound engagement with the relationship between science and art, the physical and the perceptual, the artist and the viewer. As both a historical movement and a conceptual tool, Pointillism has earned its place as a foundational chapter in the story of modern art.